Feeling safe on our streets

While walking or wheeling are for everyone, not everyone feels safe navigating our streets.

Feeling unsafe is a bigger problem in certain locations, and is more likely to affect some groups of people.

For example, research by the Office of National Statistics revealed that:

- One in two women and one in seven men felt unsafe walking alone after dark in a quiet street near their home.

- Disabled people felt less safe walking or wheeling alone in all settings than non-disabled people.

- Street harassment makes this situation worse, something women are much more likely to suffer than men.

Research by Stonewall revealed that more than two in five trans people avoid certain streets altogether because they don’t feel safe there as an LGBTQ+ person.

A UK Government survey also showed that certain demographic groups were significantly more likely to have experienced at least one form of sexual harassment in the last 12 months, these include: women, young people (ages 15-24 and 25 to 34), ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities), LGBTQ+ individuals, and those with disabilities.

This is a huge issue that needs a wide range of solutions, but good street and urban design can play their part.

Good quality streets can feel safer

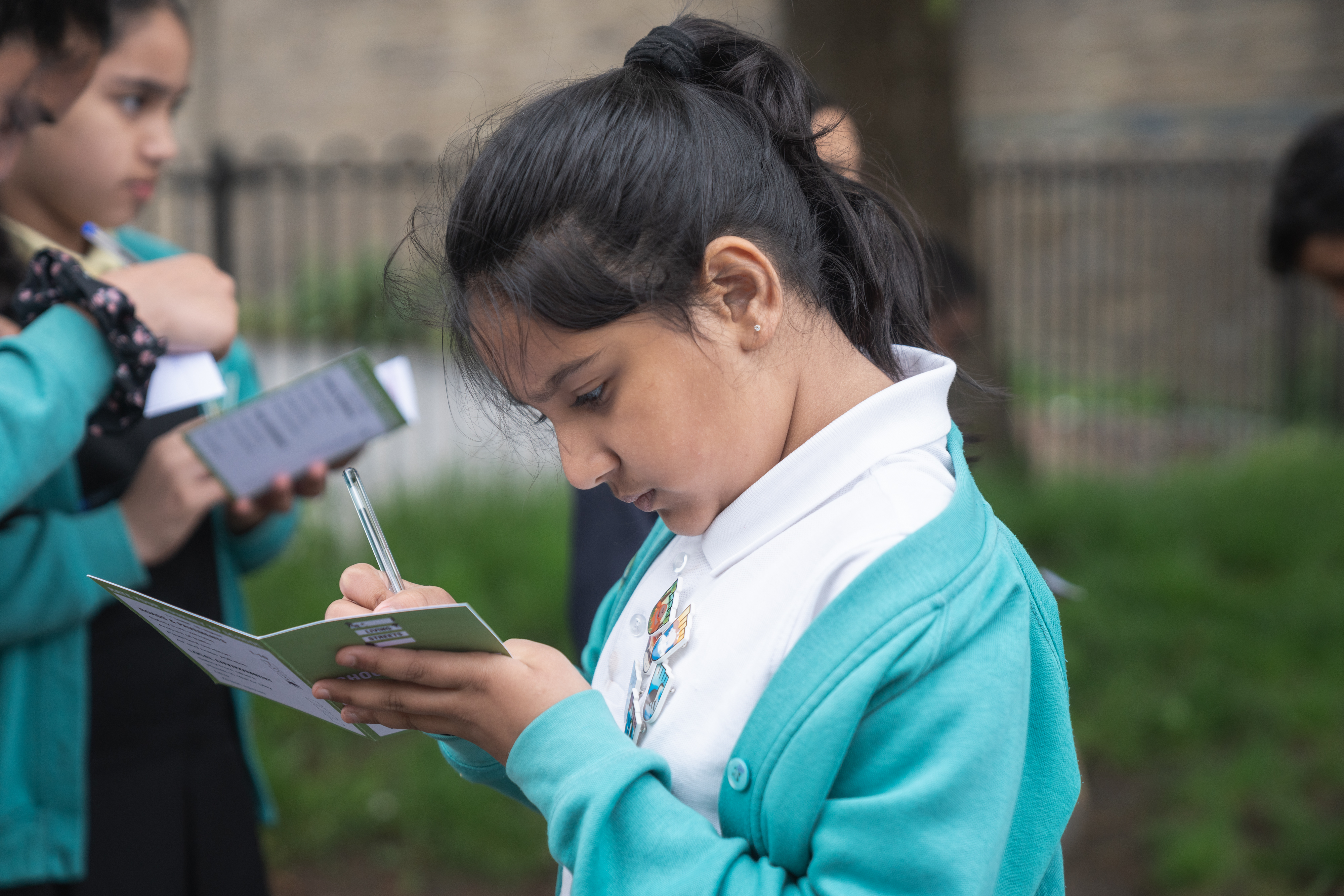

Fear of crime and anti-social behaviour is often raised on our Community Street Audits. These audits are a way to evaluate the quality of streets and spaces from the viewpoint of the people who use them.

There are a number of things that can make our streets feel less safe. Fast or heavy traffic, litter, broken pavements or poor lighting are just some examples. People often worry about walking through underpasses too.

While evidence suggests that most of us will choose the quickest or easiest walking route, many people will go out of their way to avoid areas they feel are unpleasant or dangerous.

Making sure our streets are clean, tidy and well maintained can make them feel safer.

WHAT MAKES OUR STREETS FEEL SAFE OR UNSAFE?

Positive Impact

- Streets are clean and in good repair

- Good lighting.

- Clear sightlines. Fencing and planting does not block views (passive surveillance).

- Windows (and doors) provide passive surveillance

- Active street frontages and the movement of people during the day and in the evening.

Negative impact

- Litter, tagging and streets that are in poor repair

- Lack of visibility, poor sightlines e.g. fencing or poorly maintained planting blocking views.

- Poor lighting

- No windows overlooking the street (no passive surveillance)

- Blank frontages and closed premises removing the presence of people

- Tunnels and underpasses.

PASSIVE SURVEILLANCE – MORE 'EYES ON THE STREET'

People walking and wheeling feel safer if others are able to see them, such as from windows overlooking the street or as they enter or leave buildings throughout the day.

This is called 'passive surveillance'. Having ‘more eyes on the street’ reduces crime and makes an area feel more welcoming.

For example, waiting for a bus in the dark feels safer if you're next to a late-night opening shop, because you can ask for help.

But a lack of passive surveillance doesn't necessarily mean a place feels unwelcoming after dark. Having other people around, even in passing vehicles on busy roads, sometimes improves the situation.

So as well as street features, the way buildings are designed and used – influenced by national and local planning policies – can have a direct impact on how safe places feel.

Case study: Ilford

In the 60s and 70s, the London Borough of Redbridge was reconfigured for car travel. The borough council is now keen to improve the environment for pedestrians and cyclists. They set out a vision to ensure an attractive, liveable and convenient town centre for Ilford.

They commissioned us to to carry out Community Street Audits and produce recommendations.

25% people of those surveyed specifically mentioned concerns about feeling safe or anti-social behaviour.

Overall, there was a desire to improve public areas. Greenery, artworks and lighting could all play their part. Introducing more human activity and repurposing some areas - such as the underpasses - could transform the space from threatening to welcoming.

Our work with Redbridge Council will help bring about big changes for walking around the Ilford Western Gyratory area.

It will be a key step in making Ilford a place which supports those walking or wheeling.

Read more

UK Government review

The UK Government is updating its design guidance in the Manual for Streets. As part of this process in the summer of 2021 it issued a call for evidence on personal safety.

While this review relates to England only, common issues can be found across the UK.

We responded to a call for evidence on personal safety measures on streets in England. Read via the link below.

20-MINUTE NEIGHBOURHOODS

Safety is one of the many benefits of the '20-minute neighbourhood'. This idea is about creating places in which most of people's daily needs can be met within a short walk or cycle.

The concept means more people walking and wheeling the streets. These neighbourhoods will have passive surveillance integrated into their design.

There are many other reasons to support this approach, such as improving mental and physical health, supporting local shops and businesses thrive and people seeing more of their neighbours.

Walking for everyone

Arup, Living Streets and Sustrans worked together to understand behaviours surrounding walking and explore the factors that impact people’s experience of walking.

'Walking for Everyone' is designed to support national and local governments including transport and spatial planning professionals, organisations helping to improve the lives of people who may be marginalised, and anyone helping to make walking and wheeling more inclusive.